Senior British ministers were reluctant to accept that Martin McGuinness was “genuinely” committed to the peace process in Northern Ireland, archive files have revealed.

Secretary of State Sir Patrick Mayhew also speculated whether the IRA was training in the “second 11” after claiming the paramilitary group recognised that the end of the campaign of violence was in sight.

In a meeting with Tanaiste Dick Spring, Northern Ireland Office minister Michael Ancram and other officials in February 1997, Sir Patrick discussed the intentions of republicans around the peace process.

The meeting, described as a working dinner, took place at Lancaster House in central London.

Newly released archive files from 1997 reveal that the British side had probed Mr Spring and Irish officials for their views on the intentions of the republican movement.

Officials noted that the interest from the British ministers went beyond whether there was a prospect of an early ceasefire, and included whether republicans would accept the framework document as a basis for a lasting peace agreement.

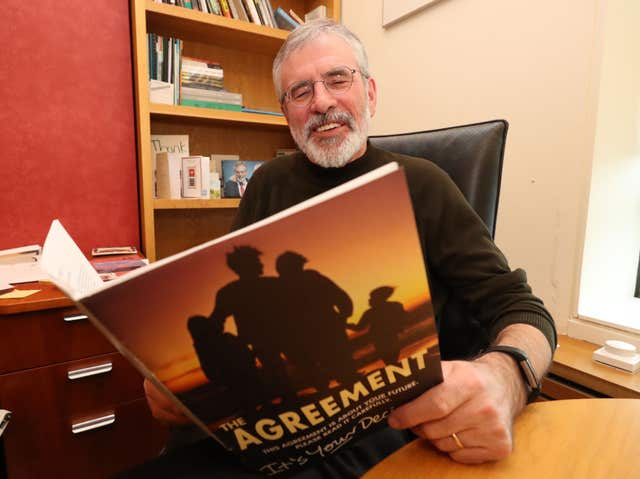

They also questioned whether republicans would accept the democratic verdict on any such agreement and whether Gerry Adams and Mr McGuinness had a “common position”.

The Secretary of State was strongly of the view that the IRA campaign was serious and that only a combination of “luck, good police work and public co-operation” had prevented a death in the recent attacks on security forces.

He felt that such a death was certain to occur soon and that this could push the loyalists over the edge.

As to why the IRA had been unusually ineffective in recent times, Sir Patrick speculated that they were training in the “second 11” and that many of the “first 11”, recognising that the end of the campaign of violence could be in sight, did “not want to be among the last to go down for 20 years”.

The record also shows that the British were interested to know whether the Irish government’s decision to restrict further meetings with Sinn Fein had produced any reaction.

Mr Spring said it would have been viewed as a political setback, particularly for Mr Adams.

The British side questioned whether the Irish side felt Mr Adams and Mr McGuinness were following the same political strategy.

Both Sir Patrick and Mr Ancram appeared reluctant to accept that Mr McGuinness was “genuinely” committed to the peace process.

Sir Patrick was assured by the Irish side that, while they were “different in personality”, the two Sinn Fein leaders were committed to a common line.

The Northern Ireland Secretary, while doubting that Sinn Fein would be able to accept an agreement which fell short of a united Ireland, said he was convinced that they had to be brought into the political process and confronted with the democratic verdict.

The document also stated that the British side went to some lengths to emphasise how far they had gone in their attempts to bring Sinn Fein into the peace process.

Mr Ancram recalled that, during the 1994 ceasefire, not only had he participated in a one-to-one-meeting with Mr McGuinness in a house in Shantallow in Derry, but that the Secretary of State had subsequently accompanied him to a further meeting held in a private house.

Asked if they were currently in contact with Sinn Fein, the British said nothing to confirm that that was the case.

The material can be viewed in the National Archives in file 2022/81/22

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here